Ove Jørgensen

Ove Jørgensen | |

|---|---|

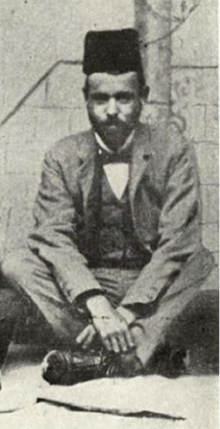

In Constantinople during his travels with Carl Nielsen, May 1903 | |

| Born | 5 September 1877 Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Died | 31 October 1950 (aged 73) |

| Burial place | Holmen Cemetery, Copenhagen |

| Known for | Jørgensen's law |

| Parent |

|

| Academic background | |

| Education | Metropolitanskolen, Copenhagen |

| Alma mater | University of Copenhagen |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Classical scholarship |

| Sub-discipline | Homeric poetry |

| Notable works | "The Appearances of the Gods in Books 9–12 of the Odyssey" (1904)[a] |

Ove Jørgensen (5 September 1877 – 31 October 1950) was a Danish scholar of classics, literature and ballet. He is known for formulating Jørgensen's law, which describes the narrative conventions used in Homeric poetry when relating the actions of the gods.

The son of Sophus Mads Jørgensen, a professor of chemistry, Jørgensen was born and lived for most of his life in Copenhagen. He was educated at the prestigious Metropolitanskolen and at the University of Copenhagen, where he began his study of the Homeric poems. In 1904, following academic travels to Berlin, Athens and Constantinople, he published "The Appearances of the Gods in Books 9–12 of the Odyssey", an article in which he outlined the distinctions between how the gods are referred to by mortal characters and by the narrator and gods in the Odyssey. The observation of these distinctions became known as "Jørgensen's law".

Jørgensen gave up classical scholarship in 1905, following a dispute with other academics after he was passed over for an invitation to a newly formed learned society. He had intended to publish a monograph based on his 1904 article, but it never materialised. Instead, he devoted himself to teaching, both at schools and at the University of Copenhagen: among his students were the future poet Johannes Weltzer and Poul Hartling, later prime minister of Denmark. He also maintained a lifelong friendship and correspondence with the composer Carl Nielsen and his wife, the sculptor Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen.

Jørgensen also published on the works of Charles Dickens and was a recognised authority on ballet. His views on the latter were conservative and nationalistic, promoting what he saw as authentic, masculine Danish aesthetics – represented by the ballet master August Bournonville – against modernist, liberalising innovations from Europe and the United States. He wrote critically of the American dancers Isadora Duncan and Loïe Fuller, but was later an advocate of the Russian choreographer Michel Fokine.

Early life and education[edit]

Ove Jørgensen was born in Copenhagen on 5 September 1877.[1] He was the son of Sophus Mads Jørgensen, a professor of chemistry at the University of Copenhagen,[2] and of Jørgensen's wife, Louise Wellmann.[3] He became a student at the prestigious Metropolitanskolen in 1895 and received his Master of Arts degree from the University of Copenhagen in 1902, submitting a thesis in which he argued for the single authorship of the Homeric poems. His university teachers included the historian Johan Ludvig Heiberg and the philologist Anders Bjørn Drachmann.[4]

Classical scholarship[edit]

Following his graduation from Copenhagen, Jørgensen travelled to Berlin, where he studied Homeric poetry under the philologists Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff and Hermann Alexander Diels. Here, he began the process of writing what became his 1904 article on the invocation of the gods in the Odyssey. On leaving Berlin, he travelled to Athens in 1903 alongside his fellow student from Copenhagen, the future archaeologist Frederik Poulsen,[5] where he met the composer Carl Nielsen and his wife Anne Marie.[6] Jørgensen became a lifelong friend of both,[7] and accompanied them to Constantinople:[8] Carl Nielsen mentions him sixty-three times in his diary.[7] Jørgensen subsequently travelled to Rome, where he cultivated an interest in Baroque art.[1]

Jørgensen published an article, "The Appearances of the Gods in Books 9–12 of the Odyssey",[a] in the journal Hermes in 1904.[9] In this article, Jørgensen observed that Homeric characters typically use generic terms, particularly θεός (theos: 'a god'), δαίμων (daimon) and Ζεύς (Zeus), to refer to the action of gods, whereas the narrator and the gods themselves always name the specific gods responsible. These principles became known as Jørgensen's law,[10] and were described in 1998 as the "standard analysis of ... the rules that govern human speech about the gods" by the classicist Ruth Scodel.[11] Jørgensen began work on a book-length treatment of his ideas, but never published it.[1]

In 1904, Jørgensen began to work as a teacher, taking a post at N. Zahle's School in Copenhagen, and another in 1905 at the Østersøgade Gymnasium in the same city. He left academia in 1905, following a dispute with other classical scholars over the founding of the Greek Society for Philhellenes,[c] a learned society founded by intellectuals including Heiberg, Harald Høffding and Georg Brandes. Although most members were qualified as doctors of philosophy, others, including Nielsen, were invited. Jørgensen was not, which he considered a snub, and he refused the offer of Drachmann to introduce him to the society.[1]

Later career[edit]

Jørgensen continued to teach the classical languages following his retreat from academic work. Among his students was the future prime minister of Denmark, Poul Hartling, who described Jørgensen as "the best teacher [he] ever had". Jørgensen taught a Greek class at the University of Copenhagen, where Hartling was a theology student between 1932 and 1939.[12] He also taught the future poet Johannes Weltzer, who wrote in 1953 that Jørgensen's classes on Plato's Apologia, a philosophical work portraying the defence of Plato's teacher Socrates against charges of impiety, were "a matter of introducing [his students] into the Socratic way of life", and that Weltzer expected few of those students to have forgotten them.[13]

Jørgensen's father, Sophus, died in 1914.[2] In 1916, working alongside the chemist S. P. L. Sørensen, Jørgensen completed and published Sophus's unfinished manuscript of Development History of the Chemical Concept of Acid until 1830.[14][d] He maintained his friendship and correspondence with Carl Nielsen,[15] who discussed Shakespeare with Jørgensen and wrote to him in 1916 about his abortive efforts to write an opera based on The Tempest, as well as about the precarious state of Nielsen's marriage.[16] Jørgensen also corresponded with Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen: in 1922, she wrote to him that she had reconciled with Carl and determined to remain with him.[17]

Jørgensen became an authority on ballet, writing a series of essays from 1905 in which he promoted what he saw as the traditional aesthetics of the Royal Danish Ballet.[1] He asserted the importance of the Danish ballet master August Bournonville while criticising the innovations introduced into European ballet by the dancer Isadora Duncan.[18] Jørgensen called Duncan "the American dilettante", denigrated her as middle-aged and under-educated, and likened her dancing movements to those of a goose.[19] He also condemned the Art Nouveau- and symbolism-influenced style of Loïe Fuller, another American who, like Duncan, performed in Denmark in 1905, calling it "quasi-philosophical experiments".[20] In March 1905, he attended a lecture by Vilhelm Wanscher, a philosopher and historian of art: Jørgensen described his conception of the aesthetic perception of art as "a mental disorder".[21]

The ballet scholar Karen Vedel has linked Jørgensen's opposition to Duncan, and the liberalising ideas of the Modern Breakthrough she represented, to the ideology of the Danish national conservative movement: in particular, through his promotion of what he saw as distinctively "Danish" ballet and his characterisation of this as masculine and Dionysian.[19] Jørgensen's nationalistic ideas about ballet softened over time: in 1908, he gave a positive review of a performance of the Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova with dancers from the Mariinsky Theatre, while in 1918 he recommended that the Russian choreographer Michel Fokine be hired by the Royal Danish Theatre.[22] In the same year, he defended Fokine against accusations that his artistic style was revolutionary in character and connected with Bolshevism.[23]

Jørgensen's other scholarly interests included the English novelist Charles Dickens:[1] Hartling later wrote that Jørgensen could easily have been a professor of his work.[24] Jørgensen edited a 1930 Danish edition of Dickens's novel Great Expectations, to which he added an introductory essay, later praised by the literary scholar Jørgen Erik Nielsen as displaying an extensive knowledge both of Dickens and of related literature and criticism.[25]

Frederik Poulsen, who knew Jørgensen in Copenhagen and Berlin and accompanied him to Athens, described him as "a quiet, reticent student" and a "remarkable man", whom he compared with Socrates.[8] Hartling described Jørgensen as looking like "what a professor ... should look like according to the clichés: scruffy-stubble full beard, thin-rimmed glasses, knee flaps and button-downs". He portrays Jørgensen's lessons as "steeped in humour", particularly Jørgensen's taste for acerbic, sarcastic comments at the expense of students who arrived late or whom he perceived to be slacking – which sometimes included Hartling.[24]

Jørgensen never married. He died in the Freeport of Copenhagen on 31 October 1950, and was buried in Holmen Cemetery.[1]

Selected works[edit]

As author[edit]

- Jørgensen, Ove (1904). "Das Auftreten der Goetter in den Buechern ι–μ der Odyssee" [The Appearances of the Gods in Books 9–12 of the Odyssey]. Hermes (in German). 39 (3): 357–382. JSTOR 4472953.

- — (1905). "Balletens Kunst" [The Art of Ballet]. Tilskueren [The Spectator] (in Danish). 22: 338–348. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- — (1906). "Duncan kontra Bournonville" [Duncan Against Bournonville]. Tilskueren [The Spectator] (in Danish). 23: 511–520. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- — (1918). "Fokin kontra Bournonville" [Fokine Against Bournonville]. Tilskueren [The Spectator] (in Danish).

- — (1971). Krabbe, Henning (ed.). Udvalgte Skrifter: Ballet, Klassik, Litteratur, Kunst [Collected Writings: Ballet, Classics, Literature, Art] (in Danish). Copenhagen: Thaning & Appel. ISBN 8741344405.

As editor[edit]

- Dickens, Charles (1930). Jørgensen, Ove (ed.). Store forventninger [Great Expectations] (in Danish). Copenhagen: Gyldendals bibliotek. OCLC 60963419.

- Jørgensen, Sophus Mads (1916). Sørensen, S. P. L.; Jørgensen, Ove (eds.). Det kemiske Syrebegrebs Udviklingshistorie indtil 1830 [Development History of the Chemical Concept of Acid until 1830] (in Danish). Copenhagen: Andr. Fred. Høst & Søn, Kgl. Hof-Boghandel. OCLC 874980879.

Footnotes[edit]

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ a b German: Das Auftreten der Goetter in den Buechern ι–μ der Odyssee[b]

- ^ Jørgensen uses the traditional Greek numbering system, by which books of the Odyssey are designated by lower-case Greek letters, and those of the Iliad are designated in upper case. See Dickey 2007, p. 132

- ^ Danish: Græsk selskab for filhellenere

- ^ Danish: Det kemiske Syrebegrebs Udviklingshistorie indtil 1830

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Hartmann 2011.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1960, p. 7.

- ^ Hartmann 2011; Kauffman 1992, p. 219.

- ^ Hartmann 2011. On the Metropolitanskolen, see Barnett 2022, p. 155; Damsholt 2011, p. 214.

- ^ Hartmann 2011; Poulsen 2023, search "Ove Jørgensen".

- ^ Fjeldsøe 2010, p. 38; Muntoni 2019, p. 56.

- ^ a b Fjeldsøe 2010, p. 38.

- ^ a b Poulsen 2023, search: "Ove Jørgensen".

- ^ Jørgensen 1904; Hartmann 2011.

- ^ Cook 2018, p. 179.

- ^ Scodel 1998, p. 179.

- ^ Hartling 2016, search "Ove Jørgensen". For Harling's dates at Copenhagen, see The International Year Book and Statesmen's Who's Who 1979, p. 307.

- ^ Weltzer 1953, p. 40.

- ^ Kauffman 1960, p. 183.

- ^ Krabbe 2020, p. 33, 34, 71–72.

- ^ Fanning & Assay 2020, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Reynolds 2020, p. 218.

- ^ Jørgensen 1905; Vedel 2020, p. 21.

- ^ a b Vedel 2020, p. 21.

- ^ Jørgensen 1906, p. 511; Broad 2020, p. 425. For Fuller's links to symbolism and Art Nouveau, see Current & Current 1997, p. 4.

- ^ Friis 1999, p. 246.

- ^ Vedel 2020, p. 22.

- ^ Vedel 2012, p. 519.

- ^ a b Hartling 2016, search "Ove Jørgensen".

- ^ Nielsen 2009, p. 209.

Works cited[edit]

- Barnett, Christopher P. (2022). Historical Dictionary of Kierkegaard's Philosophy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9781538122624.

- Broad, Leah (2020). "Scaramouche, Scaramouche: Sibelius on Stage". Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 145 (2): 417–456. doi:10.1017/rma.2020.15. S2CID 228974146.

- Cook, Erwin F. (2018). The Odyssey in Athens: Myths of Cultural Origins. New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501723506.

- Current, Richard Nelson; Current, Marcia Ewing (1997). Loie Fuller: Goddess of Light. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 9781555533090. Retrieved 28 January 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- Damsholt, Nanna (2011). "Danish Folk High School and the Creation of a New Danish Man". In Werner, Yvonne Marie (ed.). Christian Masculinity: Men and Religion in Northern Europe in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Leuven: Leuven University Press. pp. 213–232. ISBN 9789058678737.

- Dickey, Eleanor (2007). Ancient Greek Scholarship: A Guide to Finding, Reading, and Understanding Scholia, Commentaries, Lexica, and Grammatical Treatises, from Their Beginnings to the Byzantine Period. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198042662.

- Fanning, David; Assay, Michelle (2020). "Nielsen, Shakespeare and the Flute Concerto: From Character to Archetype" (PDF). Carl Nielsen Studies. 6: 68–93. doi:10.7146/cns.v6i0.122251 (inactive 3 February 2024). S2CID 224957383. Retrieved 28 January 2024 – via University of Manchester.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2024 (link) - Fjeldsøe, Michael (2010). "Carl Nielsen and the Current of Vitalism in Art". Carl Nielsen Studies. 4: 26–42.

- Friis, Eva (1999). "Et opgør med Julius Lange: kunsthistorikeren Vilhelm Wanschers æstetiske kunstopfattelse" [A Showdown with Julius Lange: The Art Historian Vilhelm Wanscher's Aesthetic Perception of Art]. Viljen til det menneskelige: Tekster omkring Julius Lange [The Will to Humanity: Texts around Julius Lange] (in Danish). Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum. pp. 233–255. ISBN 8772894547.

- "Hartling, Poul". The International Year Book and Statesmen's Who's Who. Vol. 27. Burke's Peerage. 1979.

- Hartling, Poul (2016) [1980]. Bladet i bogen: Erindringer 1914–1964 [The Leaf in the Book: Memoirs 1914–1964] (in Danish). Copenhagen: Lindhardt og Ringhof. ISBN 9788711661413.

- Hartmann, Godfred (18 July 2011). "Ove Jørgensen". Dansk Biografisk Leksikon [Danish Biographical Lexicon] (in Danish). Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- Kauffman, George B. (1960). "Sophus Mads Jørgensen and the Werner-Jørgensen Controversy". Chymia. 6: 180–204. doi:10.2307/27757198. JSTOR 27757198.

- Kauffman, George B. (1992). "Sophus Mads Jørgensen: A Danish Platinum Metals Pioneer" (PDF). Platinum Metals Review. 36: 217–223. doi:10.1595/003214092X364217223. S2CID 267564679. Retrieved 28 January 2024. [1]

- Krabbe, Niels (2020). "Nielsen's Unrealised Opera Plans" (PDF). Carl Nielsen Studies. 6: 10–67. doi:10.7146/cns.v6i0.122249 (inactive 3 February 2024). S2CID 225032852. Retrieved 28 January 2024 – via University of Manchester.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2024 (link) - Muntoni, Paolo (2019). "Simplicity and Essentiality: Carl Nielsen's Idea of Ancient Greek Music". Proceedings of the Danish Institute at Athens. 9: 55–70. doi:10.2307/j.ctv34wmvm0.6.

- Nielsen, Jørgen Erik (2009). Dickens i Danmark (in Danish). Copenhagan: Museum Tusculanum. ISBN 9788763525947.

- Poulsen, Frederik (2023) [1947]. I det gæstfrie Europa. Liv og rejser indtil første verdenskrig [In the Hospitable Europe: Life and Travels Before the First World War]. Copenhagen: Lindhardt og Ringhof. ISBN 9788728329900.

- Reynolds, Anne-Marie (2020). "Review: Carl Nielsen: Selected Letters and Diaries, selected, annotated and translated by David Fanning and Michelle Assay, Copenhagen, Museum Tusculanum, 2017" (PDF). Carl Nielsen Studies. 6: 213–220. Retrieved 28 January 2024 – via University of Manchester.

- Scodel, Ruth (1998). "Bardic Performance and Oral Tradition in Homer". The American Journal of Philology. 119 (2): 171–194. doi:10.1353/ajp.1998.0027. JSTOR 1562083. S2CID 161072518.

- Vedel, Karen (2012). "Dancing Across Copenhagen". In van den Berg, Hubert; Hautamäki, Irmeli; Hjartarson, Benedikt; Jelsbak, Torben; Schönström, Rikard; Stounbjerg, Per; Ørum, Tania; Aagesen, Dorthe (eds.). A Cultural History of the Avant-Garde in the Nordic Countries 1900–1925. Leiden: Brill. pp. 511–528. ISBN 9789401208918. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- Vedel, Karen (2020). "Out and at Home". From Local to Global: Interrogating Performance Histories. Stockholm: Theatre Studies Department, Stockholm University. pp. 21–25. OL 50566771M.

- Weltzer, Johannes (1953). De usandsynlige hverdage, en art levnedsbog [The Unlikely Weekdays: A Kind of Biography] (in Danish). Copenhagen: Nyt Nordisk Forlag. OCLC 13381955.