Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago (/ˈtrɪnɪdæd ... təˈbeɪɡoʊ/ ⓘ, /- toʊ-/, TRIH-nih-dad ... tə-BAY-goh, - toh-), officially the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, is the southernmost island country in the Caribbean. Consisting of the main islands Trinidad and Tobago and numerous much smaller islands, it is situated 11 kilometres (6.8 miles) off the coast of northeastern Venezuela and 130 kilometres (81 miles) south of Grenada.[11] It shares maritime boundaries with Barbados to the east, Grenada to the northwest and Venezuela to the south and west.[12][13] Trinidad and Tobago is generally considered to be part of the West Indies. The island country's capital is Port of Spain, while its largest and most populous city is San Fernando.

The island of Trinidad was inhabited for centuries by Indigenous peoples before becoming a colony in the Spanish Empire, following the arrival of Christopher Columbus, in 1498. Spanish governor José María Chacón surrendered the island to a British fleet under the command of Sir Ralph Abercromby in 1797.[14] Trinidad and Tobago were ceded to Britain in 1802 under the Treaty of Amiens as separate states and unified in 1889.[15] Trinidad and Tobago obtained independence in 1962, becoming a republic in 1976.[16][11]

Unlike most Caribbean nations and territories, which rely heavily on tourism, the economy is primarily industrial with an emphasis on petroleum and petrochemicals;[17] much of the nation's wealth is derived from its large reserves of oil and natural gas.[18]

Trinidad and Tobago is well known for its African and Indian cultures, reflected in its large and famous Carnival, Diwali, and Hosay celebrations, as well as being the birthplace of steelpan, the limbo, and music styles such as calypso, soca, rapso, parang, chutney, and chutney soca.

Toponymy[edit]

Historian E. L. Joseph claimed that Trinidad's Indigenous name was Cairi or "Land of the Humming Bird", derived from the Arawak name for hummingbird, ierèttê or yerettê. However, other authors dispute this etymology with some claiming that cairi does not mean hummingbird (tukusi or tucuchi being suggested as the correct word) and some claiming that kairi, or iere, simply means island.[19] Christopher Columbus renamed it "La Isla de la Trinidad" ("The Island of the Trinity"), fulfilling a vow made before setting out on his third voyage of exploration.[20] Tobago's cigar-like shape, or the use of tobacco by the native people, may have given it its Spanish name (cabaco, tavaco, tobacco) and possibly some of its other Indigenous names, such as Aloubaéra (black conch) and Urupaina (big snail),[19] although the English pronunciation is /təˈbeɪɡoʊ/. Indo-Trinidadians called the island Chinidat or Chinidad which translated to the land of sugar. The usage of the term goes back to the 19th century when recruiters in India would call the island Chinidat as a way of luring workers into indentureship on the sugar plantations.[21]

History[edit]

Geological history[edit]

The islands that make up modern-day Trinidad and Tobago lie at the southern end of the Lesser Antilles group.

Indigenous peoples[edit]

Both Trinidad and Tobago were originally settled by Indigenous people who came through South America.[11] Trinidad was first settled by pre-agricultural Archaic people at least 7,000 years ago, making it the earliest settled part of the Caribbean.[22] Banwari Trace in south-west Trinidad is the oldest attested archaeological site in the Caribbean, dating to about 5000 BC. Several waves of migration occurred over the following centuries, which can be identified by differences in their archaeological remains.[23] At the time of European contact, Trinidad was occupied by various Arawakan-speaking groups including the Nepoya and Suppoya, and Cariban-speaking groups such as the Yao, while Tobago was occupied by the Island Caribs and Galibi.

European colonization[edit]

Christopher Columbus was the first European to see Trinidad, on his third voyage to the Americas in 1498.[22][24] He also reported seeing Tobago on the distant horizon, naming it Bellaforma, but did not land on the island.[11][25]

In the 1530s Antonio de Sedeño, a Spanish soldier intent on conquering the island of Trinidad, landed on its southwest coast with a small army of men, intending to subdue the Indigenous population of the island. Sedeño and his men fought the native peoples on many occasions, and subsequently built a fort. The next few decades were generally spent in warfare with the native peoples, until in 1592, the "Cacique" (native chief) Wannawanare (also known as Guanaguanare) granted the area around modern Saint Joseph to Domingo de Vera e Ibargüen, and withdrew to another part of the island.[19] The settlement of San José de Oruña was later established by Antonio de Berrío on this land in 1592.[11][22] Shortly thereafter the English sailor Sir Walter Raleigh arrived in Trinidad on 22 March 1595 in search of the long-rumoured "El Dorado" ("City of Gold") supposedly located in South America.[22] He attacked San José, captured and interrogated Antonio de Berrío, and obtained much information from him and from the Cacique Topiawari; Raleigh then went on his way, and Spanish authority was restored.[26]

Meanwhile, there were numerous attempts by European powers to settle Tobago during the 1620–40s, with the Dutch, English and Couronians (people from the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, now part of Latvia) all attempting to colonise the island with little success.[27][28] From 1654 the Dutch and Courlanders managed to gain a more secure foothold, later joined by several hundred French settlers.[27] A plantation economy developed based on the production of sugar, indigo and rum, worked by large numbers of African slaves who soon came to vastly outnumber the European colonists.[28][27] Large numbers of forts were constructed as Tobago became a source of contention between France, Netherlands and Britain, with the island changing hands some 31 times prior to 1814, a situation exacerbated by widespread piracy.[28] The British managed to hold Tobago from 1762 to 1781, whereupon it was captured by the French, who ruled until 1793 when Britain re-captured the island.[28]

The 17th century on Trinidad passed largely without major incident, but sustained attempts by the Spaniards to control and rule over the Indigenous population was often fiercely resisted.[22] In 1687 the Catholic Catalan Capuchin friars were given responsibility for the conversions of the indigenous people of Trinidad and the Guianas.[22] They founded several missions in Trinidad, supported and richly funded by the state, which also granted encomienda right to them over the native peoples, in which the native peoples were forced to provide labour for the Spanish.[22] One such mission was Santa Rosa de Arima, established in 1689, when Indigenous people from the former encomiendas of Tacarigua and Arauca (Arouca) were relocated further west.[citation needed] Escalating tensions between the Spaniards and Indigenous people culminated in violence in 1689, when Indigenous people in the San Rafael encomienda rebelled and killed several priests, attacked a church, and killed the Spanish governor José de León y Echales. Among those killed in the governor's party was Juan Mazien de Sotomayor, missionary priest to the Nepuyo villages of Caura, Tacarigua and Arauca.[29] The Spanish retaliated severely, slaughtering hundreds of native peoples in an event that became known as the Arena massacre.[22] As a result, continuing Spanish slave-raiding, and the devastating impact of introduced disease to which they had no immunity, the native population was virtually wiped out by the end of the following century.[30][22]

During this period Trinidad was an island province belonging to the Viceroyalty of New Spain, together with Central America, present-day Mexico and what would later become the southwestern United States.[31] In 1757 the capital was moved from San José de Oruña to Puerto de España (modern Port of Spain) following several pirate attacks.[32] However the Spanish never made any concerted effort to colonise the islands; Trinidad in this period was still mostly forest, populated by a few Spaniards with a handful of slaves and a few thousand Indigenous people.[31] Indeed, the population in 1777 was only 1,400, and Spanish colonisation in Trinidad remained tenuous.[citation needed]

Influx of French settlers[edit]

In 1777, the captain general Luis de Unzaga 'le Conciliateur', married to a French Creole, allowed free trade in Trinidad, attracting French settlers and its economy improved notably.[33] Since Trinidad was considered underpopulated, Roume de St. Laurent, a Frenchman living in Grenada, was able to obtain a Cédula de Población from the Spanish king Charles III on 4 November 1783.[34] A Cédula de Población had previously been granted in 1776 by the king, but had not shown results, and therefore the new Cédula was more generous.[11] It granted free land and tax exemption for 10 years to Roman Catholic foreign settlers who were willing to swear allegiance to the King of Spain.[11] The land grant was 30 fanegas (13 hectares/32 acres) for each free man, woman and child and half of that for each slave that they brought with them. The Spanish sent a new governor, José María Chacón, to implement the terms of the new cédula.[34]

The Cédula was issued only a few years before the French Revolution. During that period of upheaval, French planters with their slaves, free coloureds and mulattos from the neighbouring islands of Martinique, Saint Lucia, Grenada, Guadeloupe and Dominica migrated to Trinidad, where they established an agriculture-based economy (sugar and cocoa).[31] These new immigrants established local communities in Blanchisseuse, Champs Fleurs, Paramin,[35] Cascade, Carenage and Laventille.

As a result, Trinidad's population jumped to over 15,000 by the end of 1789, and by 1797 the population of Port of Spain had increased from under 3,000 to 10,422 in just five years, with a varied population of mixed race individuals, Spaniards, Africans, French republican soldiers, retired pirates and French nobility.[31] The total population of Trinidad was 17,718, of which 2,151 were of European ancestry, 4,476 were "free blacks and people of colour", 10,009 were enslaved people and 1,082 Indigenous people.[citation needed] The sparse settlement and slow rate of population-increase during Spanish rule (and even later during British rule) made Trinidad one of the less populated colonies of the West Indies, with the least developed plantation infrastructure.[36]

British rule[edit]

.JPG/170px-Trinidad_Ralph_Abercromby_(cropped).JPG)

The British had begun to take a keen interest in Trinidad, and in 1797 a British force led by General Sir Ralph Abercromby launched an invasion of Trinidad.[11][37] His squadron sailed through the Bocas and anchored off the coast of Chaguaramas. Seriously outnumbered, Chacón decided to capitulate to the British without fighting.[37] Trinidad thus became a British crown colony, with a largely French-speaking population and Spanish laws.[31] British rule was later formalised under the Treaty of Amiens (1802).[11][37] The colony's first British governor was Thomas Picton, however his heavy-handed approach to enforcing British authority, including the use of torture and arbitrary arrest, led to his being recalled.[37]

British rule led to an influx of settlers from the United Kingdom and the British colonies of the Eastern Caribbean. English, Scots, Irish, German and Italian families arrived, as well as some free blacks known as "Merikins" who had fought for Britain in the War of 1812 and were granted land in southern Trinidad.[38][39][40] Under British rule, new states were created and the importation of slaves increased, however by this time support for abolitionism had vastly increased and in England the slave trade was under attack.[36][41] Slavery was abolished in 1833, after which former slaves served an "apprenticeship" period. In 1837 Daaga, a West African slave trader who had been captured by Portuguese slavers and later rescued by the British navy, was conscripted into the local regiment. Daaga and a group of his compatriots mutinied at the barracks in St Joseph and set out eastward in an attempt to return to their homeland. The mutineers were ambushed by a militia unit just outside the town of Arima. The revolt was crushed at the cost of some 40 dead, and Daaga and his party were later executed at St Joseph.[42] The apprenticeship system ended on 1 August 1838 with full emancipation.[11][40] An overview of the population statistics in 1838, however, clearly reveals the contrast between Trinidad and its neighbouring islands: upon emancipation of the slaves in 1838, Trinidad had only 17,439 slaves, with 80% of slave owners having enslaved fewer than 10 people each.[43] In contrast, at twice the size of Trinidad, Jamaica had roughly 360,000 slaves.[44]

Arrival of Indian indentured labourers[edit]

After the African slaves were emancipated many refused to continue working on the plantations, often moving out to urban areas such as Laventille and Belmont to the east of Port of Spain.[40] As a result, a severe agricultural labour shortage emerged. The British filled this gap by instituting a system of indentureship. Various nationalities were contracted under this system, including Indians, Chinese, and Portuguese.[45] Of these, the East Indians were imported in the largest numbers, starting from 1 May 1845, when 225 Indians were brought in the first ship to Trinidad on the Fatel Razack, a Muslim-owned vessel.[40][46] Indentureship of the Indians lasted from 1845 to 1917, during which time more than 147,000 Indians came to Trinidad to work on sugarcane plantations.[11][47]

Indentureship contracts were sometimes exploitative, to such an extent that historians such as Hugh Tinker were to call it "a new system of slavery". Despite these descriptions, it was not truly a new form of slavery, as workers were paid, contracts were finite, and the idea of an individual being another's property had been eliminated when slavery was abolished.[48] In addition, employers of indentured labour had no legal right to flog or whip their workers; the main legal sanction for the enforcement of the indenture laws was prosecution in the courts, followed by fines or (more likely) jail sentences.[49] People were contracted for a period of five years, with a daily wage as low as 25 cents in the early 20th century, and they were guaranteed return passage to India at the end of their contract period. However, coercive means were often used to retain labourers, and the indentureship contracts were soon extended to 10 years from 1854 after the planters complained that they were losing their labour too early.[36][40] In lieu of the return passage, the British authorities soon began offering portions of land to encourage settlement, and by 1902, more than half of the sugar cane in Trinidad was being produced by independent cane farmers; the majority of which were Indians.[50] Despite the trying conditions experienced under the indenture system, about 90% of the Indian immigrants chose, at the end of their contracted periods of indenture, to make Trinidad their permanent home.[51] Indians entering the colony were also subject to certain crown laws which segregated them from the rest of Trinidad and Tobago's population, such as the requirement that they carry a pass with them if they left the plantations, and that if freed, they carry their "Free Papers" or certificate indicating completion of the indenture period.[52]

.svg/220px-Flag_of_Trinidad_and_Tobago_(1889–1958).svg.png)

| Trinidad and Tobago Act 1887 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg/140px-Royal_Coat_of_Arms_of_the_United_Kingdom_(variant_1%2C_1952-2022).svg.png) | |

| Long title | An Act to enable Her Majesty by Order in Council to unite the Colonies of Trinidad and Tobago into one Colony. |

| Citation | 50 & 51 Vict. c. 44 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 16 September 1887 |

| Commencement | 16 September 1887 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

Few Indians settled on Tobago however, and the descendants of African slaves continued to form the majority of the island's population. An ongoing economic slump in the middle-to-late 19th century caused widespread poverty.[53] Discontent erupted into rioting on the Roxborough plantation in 1876, in an event known as the Belmanna Uprising after a policeman who was killed.[53] The British eventually managed to restore control, however, as a result of the disturbances Tobago's Legislative Assembly voted to dissolve itself and the island became a Crown colony in 1877.[53] With the sugar industry in a state of near-collapse and the island no longer profitable, the British attached Tobago to their Trinidad colony in 1889.[11][54][55]

Early 20th century[edit]

In 1903, a protest against the introduction of new water rates in Port of Spain erupted into rioting; 18 people were shot dead, and the Red House (the government headquarters) was damaged by fire.[54] A local elected assembly with some limited powers was introduced in 1913.[54] Economically Trinidad and Tobago remained a predominantly agricultural colony; alongside sugarcane, the cacao (cocoa) crop also contributed greatly to economic earnings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In November 1919, the dockworkers went on strike over bad management practices, low wages compared to a higher cost of living.[56] Strikebreakers were brought in to keep a minimum of goods moving through the ports. On 1 December 1919, the striking dockworkers rushed the harbour and chased off the strikebreakers.[56] They then proceeded to march on the government buildings in Port of Spain. Other unions and workers, many with the same grievances, joined the dock worker's strike making it a General Strike.[56] Violence broke out and was only put down with help from the sailors of British Naval ship HMS Calcutta. The unity brought upon by the strike was the first time of cooperation between the various ethnic groups of the time.[57] Historian Brinsley Samaroo says that the 1919 strikes "seem to indicate that there was a growing class consciousness after the war and this transcended racial feelings at times."[57]

However, in the 1920s, the collapse of the sugarcane industry, concomitant with the failure of the cocoa industry, resulted in widespread depression among the rural and agricultural workers in Trinidad, and encouraged the rise of a labour movement. Conditions on the islands worsened in the 1930s with the onset of the Great Depression, with an outbreak of labour riots occurring in 1937 which resulted in several deaths.[58] The labour movement aimed to unite the urban working class and agricultural labour class; the key figures being Arthur Cipriani, who led the Trinidad Labour Party (TLP), Tubal Uriah "Buzz" Butler of the British Empire Citizens' and Workers' Home Rule Party, and Adrian Cola Rienzi, who led the Trinidad Citizens League (TCL), Oilfields Workers' Trade Union, and All Trinidad Sugar Estates and Factory Workers Union.[58] As the movement developed calls for greater autonomy from British colonial rule became widespread; this effort was severely undermined by the British Home Office and by the British-educated Trinidadian elite, many of whom were descended from the plantocracy class.

Petroleum had been discovered in 1857, but became economically significant only in the 1930s and afterwards as a result of the collapse of sugarcane and cocoa, and increasing industrialization.[59][60][61] By the 1950s petroleum had become a staple in Trinidad's export market, and was responsible for a growing middle class among all sections of the Trinidad population. The collapse of Trinidad's major agricultural commodities, followed by the Depression, and the rise of the oil economy, led to major changes in the country's social structure.

The presence of American military bases in Chaguaramas and Cumuto in Trinidad during World War II had a profound effect on society. The Americans vastly improved the infrastructure on Trinidad and provided many locals with well-paying jobs; however, the social effects of having so many young soldiers stationed on the island, as well as their often unconcealed racial prejudice, caused resentment.[54] The Americans left in 1961.[62]

In the post-war period the British began a process of decolonisation across the British Empire. In 1945 universal suffrage was introduced to Trinidad and Tobago.[11][54] Political parties emerged on the island, however these were largely divided along racial lines: Afro-Trinidadians and Tobagonians primarily supported the People's National Movement (PNM), formed in 1956 by Eric Williams, with Indo-Trinidadians and Tobagonians mostly supporting the People's Democratic Party (PDP), formed in 1953 by Bhadase Sagan Maraj,[63] which later merged into the Democratic Labour Party (DLP) in 1957.[64] Britain's Caribbean colonies formed the West Indies Federation in 1958 as a vehicle for independence, however the Federation dissolved after Jamaica withdrew following a membership referendum in 1961. The government of Trinidad and Tobago subsequently chose to seek independence from the United Kingdom on its own.[65]

Contemporary era[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago gained its independence from the United Kingdom on 31 August 1962.[11][61] However, Elizabeth II remained head of state, represented locally by Governor-General Solomon Hochoy, until the passage of the 1976 Republican Constitution.[66]

Eric Williams of the People's National Movement became the first Prime Minister, serving in that capacity uninterrupted until 1981.[11] The dominant figure in the opposition in the early independence years was Opposition Leader Rudranath Capildeo of the Democratic Labour Party. The first Speaker of the House of Representatives was Clytus Arnold Thomasos and the first President of the Senate was J. Hamilton Maurice. The 1960s saw the rise of a Black Power movement, inspired in part by the civil rights movement in the United States. Protests and strikes became common, with events coming to head in April 1970 when police shot dead a protester named Basil Davis.[64] Fearing a breakdown of law and order, Prime Minister Williams declared a state of emergency and ordered that many of the Black Power leaders be arrested. Some army leaders who were sympathetic to the Black Power movement, notably Raffique Shah and Rex Lassalle, attempted to mutiny; however, this was quashed by the Trinidad and Tobago Coast Guard.[64] Williams and the PNM retained power, largely due to divisions in the opposition.[64]

In 1963 Tobago was struck by Hurricane Flora, which killed 30 people and resulted in enormous destruction across the island.[67] Partly as a result of this, tourism came to replace agriculture as the island's primary source of income in the subsequent decades.[67] On 1 May 1968, Trinidad and Tobago joined the Caribbean Free Trade Association (CARIFTA), which provided a continued economic, rather than political, linkage between the former British West Indies English-speaking countries after the West Indies Federation failed. On 1 August 1973, the country became a founding member state of CARIFTA's successor, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), which is a political and economic union between several Caribbean countries and territories.

Between the years 1972 and 1983, the country profited greatly from the rising price of oil and the discovery of vast new oil deposits in its territorial waters, resulting in an economic boom that substantially increased living standards.[11][64] In 1976 the country became a republic within the Commonwealth, though it retained the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council as its final appellate court.[11] The position of governor-general was replaced with that of President; Ellis Clarke was the first to hold this largely ceremonial role.[68] Tobago was granted limited self-rule with the creation of the Tobago House of Assembly in 1980.[53]

Williams died in 1981, being replaced by George Chambers who led the country until 1986. By this time a fall in the price of oil had resulted in a recession, causing rising inflation and unemployment.[69] The main opposition parties united under the banner of National Alliance for Reconstruction (NAR) and won the 1986 Trinidad and Tobago general election, with NAR leader A. N. R. Robinson becoming the new Prime Minister.[70][64] Robinson was unable to hold together the fragile NAR coalition, and his economic reforms, such as the implementation of an International Monetary Fund Structural Adjustment Program and devaluation of currency led to social unrest.[11] In 1990, 114 members of the Jamaat al Muslimeen, led by Yasin Abu Bakr (formerly known as Lennox Phillip) stormed the Red House (the seat of Parliament), and Trinidad and Tobago Television, the only television station in the country at the time, holding Robinson and country's government hostage for six days before surrendering.[71] The coup leaders were promised amnesty, but upon their surrender they were arrested, ultimately being released after protracted legal wrangling.[45]

The PNM under Patrick Manning returned to power following the 1991 Trinidad and Tobago general election.[11] Hoping to capitalise on an improvement in the economy, Manning called an early election in 1995, however, this resulted in a hung parliament. Two NAR representatives backed the opposition United National Congress (UNC), which had split off from the NAR in 1989, and they thus took power under Basdeo Panday, who became the country's first Indo-Trinidadian Prime Minister.[11][69][72] After a period of political confusion caused by a series of inconclusive election results, Patrick Manning returned to power in 2001, retaining that position until 2010.[11]

In 2003 the country entered a second oil boom, and petroleum, petrochemicals and natural gas continue to be the backbone of the economy. Tourism and the public service are the mainstay of the economy of Tobago, though authorities have attempted to diversify the island's economy.[73] A corruption scandal resulted in Manning's defeat by the newly formed People's Partnership coalition in 2010, with Kamla Persad-Bissessar becoming the country's first female Prime Minister.[74][75][76] However, corruption allegations bedevilled the new administration, and the PP were defeated in 2015 by the PNM under Keith Rowley.[77][78] In August 2020, the governing People's National Movement won general election, earning the incumbent Prime Minister Keith Rowley a second term in office.[79]

Geography[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago is situated between 10° 2' and 11° 12' N latitude and 60° 30' and 61° 56' W longitude, with the Caribbean Sea to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east and south, and the Gulf of Paria to the west. It is located in the far south-east of the Caribbean region, with the island of Trinidad being just 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) off the coast of Venezuela in mainland South America across the Columbus Channel.[11] The islands are a physiographical extension of South America.[80] Covering an area of 5,128 km2 (1,980 sq mi),[81] the country consists of two main islands, Trinidad and Tobago, separated by a 20-mile (32 km) strait, plus a number of much smaller islands, including Chacachacare, Monos, Huevos, Gaspar Grande (or Gasparee), Little Tobago, and Saint Giles Island.[11]

Trinidad is 4,768 km2 (1,841 sq mi) in area (comprising 93.0% of the country's total area) with an average length of 80 kilometres (50 mi) and an average width of 59 kilometres (37 mi). Tobago has an area of about 300 km2 (120 sq mi), or 5.8% of the country's area, is 41 km (25 mi) long and 12 km (7.5 mi) at its greatest width. Trinidad and Tobago lie on the continental shelf of South America, and are thus geologically considered to lie entirely in South America.[11]

The terrain of the islands is a mixture of mountains and plains.[16] On Trinidad the Northern Range runs parallel with the north coast, and contains the country's highest peak (El Cerro del Aripo), which is 940 metres (3,080 ft) above sea level,[16] and second highest (El Tucuche, 936 metres (3,071 ft)).[11] The rest of the island is generally flatter, excluding the Central Range and Montserrat Hills in the centre of the island and the Southern Range and Trinity Hills in the south. The three mountain ranges determine the drainage pattern of Trinidad.[80] The east coast is noted for its beaches, most notably Manzanilla Beach. The island contains several large swamp areas, such as the Caroni Swamp and the Nariva Swamp.[11] Major bodies of water on Trinidad include the Hollis Reservoir, Navet Reservoir, Caroni Reservoir. Trinidad is made up of a variety of soil types, the majority being fine sands and heavy clays. The alluvial valleys of the Northern Range and the soils of the East–West Corridor are the most fertile.[82][citation needed] Trinidad is also notable for containing Pitch Lake, the largest natural reservoir of asphalt in the world.[16][11] Tobago contains a flat plain in its south-west, with the eastern half of the island being more mountainous, culminating in Pigeon Peak, the island's highest point at 550 metres (1,800 ft).[83] Tobago also contains several coral reefs off its coast.[11]

The majority of the population reside on the island of Trinidad, and this is thus the location of largest towns and cities. There are four major municipalities in Trinidad: the capital Port of Spain, San Fernando, Arima and Chaguanas. The main town on Tobago is Scarborough.

Geology[edit]

The Northern Range consists mainly of Upper Jurassic and Cretaceous metamorphic rocks. The Northern Lowlands (the East–West Corridor and Caroni Plain) consist of younger shallow marine clastic sediments. South of this, the Central Range fold and thrust belt consists of Cretaceous and Eocene sedimentary rocks, with Miocene formations along the southern and eastern flanks. The Naparima Plain and the Nariva Swamp form the southern shoulder of this uplift.[citation needed]

The Southern Lowlands consist of Miocene and Pliocene sands, clays, and gravels. These overlie oil and natural gas deposits, especially north of the Los Bajos Fault. The Southern Range forms the third anticlinal uplift. The rocks consist of sandstones, shales, siltstones and clays formed in the Miocene and uplifted in the Pleistocene. Oil sands and mud volcanoes are especially common in this area.[citation needed]

Climate[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago has a maritime tropical climate.[16][11] There are two seasons annually: the dry season for the first five months of the year, and the rainy season in the remaining seven of the year. Winds are predominantly from the northeast and are dominated by the northeast trade winds. Unlike many Caribbean islands Trinidad and Tobago lies outside the main hurricane alleys; nevertheless, the island of Tobago was struck by Hurricane Flora on 30 September 1963. In the Northern Range of Trinidad, the climate is often cooler than that of the sweltering heat of the plains below, due to constant cloud and mist cover, and heavy rains in the mountains.

Record temperatures for Trinidad and Tobago are 39 °C (102 °F)[84] for the high in Port of Spain, and a low of 12 °C (54 °F).[85]

Biodiversity[edit]

Because Trinidad and Tobago lies on the continental shelf of South America, and in ancient times were physically connected to the South American mainland, its biological diversity is unlike that of most other Caribbean islands, and has much more in common with that of Venezuela.[86] The main ecosystems are: coastal and marine (coral reefs, mangrove swamps, open ocean and seagrass beds); forest; freshwater (rivers and streams); karst; man-made ecosystems (agricultural land, freshwater dams, secondary forest); and savanna. On 1 August 1996, Trinidad and Tobago ratified the 1992 Rio Convention on Biological Diversity, and it has produced a biodiversity action plan and four reports describing the country's contribution to biodiversity conservation. These reports formally acknowledged the importance of biodiversity to the well-being of the country's people through provision of ecosystem services.[87]

.jpg/220px-Leatherback_sea_turtle_Tinglar%2C_USVI_(5839996547).jpg)

Information about vertebrates is good, with 472 bird species (2 endemics), about 100 mammals, about 90 reptiles (a few endemics), about 30 amphibians (including several endemics), 50 freshwater fish and at least 950 marine fish.[88] Notable mammal species include the ocelot, West Indian manatee, collared peccary (known as the quenk locally), red-rumped agouti, lappe, red brocket deer, Neotropical otter, weeper capuchin and red howler monkey; there are also some 70 species of bat, including the vampire bat and fringe-lipped bat.[11][89] The larger reptiles present include 5 species of marine turtles known to nest on the islands' beaches, the green anaconda, the Boa constrictor and the spectacled caiman. There are at least 47 species of snakes, including only four dangerous venomous species (only in Trinidad and not in Tobago), lizards such as the green iguana, the Tupinambis cryptus and a few species of fresh water turtles and land tortoises.[11][90] are present. Of the amphibians, the golden tree frog and Trinidad poison frog are found in the highest peaks of Trinidad's Northern Range and nearby on Venezuela's Paria Peninsula.[90][91] Marine life is abundant, with several species of sea urchin, coral, lobster, sea anemone, starfish, manta ray, dolphin, porpoise and whale shark present in the islands' waters.[92] The introduced Pterois is viewed as a pest, as it eats many native species of fish and has no natural predators; efforts are currently underway to cull the numbers of this species.[92] The country contains five terrestrial ecoregions: Trinidad and Tobago moist forests, Lesser Antillean dry forests, Trinidad and Tobago dry forests, Windward Islands xeric scrub, and Trinidad mangroves.[93]

Trinidad and Tobago is noted particularly for its large number of bird species, and is a popular destination for bird watchers. Notable species include the scarlet ibis, cocrico, egret, shiny cowbird, bananaquit, oilbird and various species of honeycreeper, trogon, toucan, parrot, tanager, woodpecker, antbird, kites, hawks, boobies, pelicans and vultures; there are also 17 species of hummingbird, including the tufted coquette which is the world's third smallest.[94]

Information about invertebrates is dispersed and very incomplete. About 650 butterflies,[88] at least 672 beetles (from Tobago alone)[95] and 40 corals[88] have been recorded.[88] Other notable invertebrates include the cockroach, leaf-cutter ant and numerous species of mosquitoes, termites, spiders and tarantulas.

Although the list is far from complete, 1,647 species of fungi, including lichens, have been recorded.[96][97][98] The true total number of fungi is likely to be far higher, given the generally accepted estimate that only about 7% of all fungi worldwide have so far been discovered.[99] A first effort to estimate the number of endemic fungi tentatively listed 407 species.[100]

Information about micro-organisms is dispersed and very incomplete. Nearly 200 species of marine algae have been recorded.[88] The true total number of micro-organism species must be much higher.

Thanks to a recently published checklist, plant diversity in Trinidad and Tobago is well documented with about 3,300 species (59 endemic) recorded.[88] Despite significant felling, forests still cover about 40% of the country, and there are about 350 different species of tree.[86] A notable tree is the manchineel which is extremely poisonous to humans, and even just touching its sap can cause severe blistering of the skin; the tree is often covered with warning signs. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.62/10, ranking it 69th globally out of 172 countries.[101]

Threats to the country's biodiversity include over-hunting and poaching (see Hunting#Trinidad and Tobago), habitat loss and fragmentation (particularly due to forest fires and land clearance for quarrying, agriculture, squatting, housing and industrial development and road construction), water pollution, and introduction of invasive species and pathogens.

Government and politics[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago is a republic with a two-party system and a bicameral parliamentary system based on the Westminster System.[16]

The head of state of Trinidad and Tobago is the president, currently Christine Kangaloo.[16] This largely ceremonial role replaced that of the governor-general (representing the monarch of Trinidad and Tobago) upon Trinidad and Tobago's becoming a republic in 1976.[11] The head of government is the prime minister, currently Keith Rowley.[16] The president is elected by an Electoral college consisting of the full membership of both houses of Parliament.

Following a general election, which takes place every five years, the president appoints as prime minister the person who has the support of a majority in the House of Representatives; this has generally been the leader of the party which won the most seats in the election (except in the case of the 2001 General Elections).[11]

Since 1980 Tobago has also had its own elections, separate from the general elections. In these elections, members are elected and serve in the unicameral Tobago House of Assembly.[16][11][102]

Parliament consists of the Senate (31 seats) and the House of Representatives (41 seats, plus the Speaker).[16][103] The members of the Senate are appointed by the president; 16 government senators are appointed on the advice of the prime minister, six opposition senators are appointed on the advice of the leader of the opposition, currently Kamla Persad-Bissessar, and nine independent senators are appointed by the president to represent other sectors of civil society. The 41 members of the House of Representatives are elected by the people for a maximum term of five years in a "first past the post" system.

Administrative divisions[edit]

Trinidad is split into 14 regions and municipalities, consisting of nine regions and five municipalities, which have a limited level of autonomy.[16][11] The various councils are made up of a mixture of elected and appointed members. Elections are held every three years.[citation needed] Tobago is administered by the Tobago House of Assembly. The country was formerly divided into counties.

Political culture[edit]

The two main parties are the People's National Movement (PNM) and the United National Congress (UNC). Support for these parties appears to fall along ethnic lines, with the PNM consistently obtaining a majority of Afro-Trinidadian vote, and the UNC gaining a majority of Indo-Trinidadian support. Several smaller parties also exist. As of the August 2020 General Elections, there were 19 registered political parties. These include, the Progressive Empowerment Party, Trinidad Humanity Campaign, New National Vision, Movement for Social Justice, Congress of the People, Movement for National Development, Progressive Democratic Patriots, National Coalition for Transformation, Progressive Party, Independent Liberal Party, Democratic Party of Trinidad and Tobago, National Organisation of We the People, Unrepresented Peoples Party, Trinidad and Tobago Democratic Front, The National Party, One Tobago Voice, and Unity of the Peoples.[104]

Military[edit]

The Trinidad and Tobago Defence Force (TTDF) is the military organisation responsible for the defence of the twin island Republic of Trinidad and Tobago.[16] It consists of the Regiment, the Coast Guard, the Air Guard and the Defence Force Reserves. Established in 1962 after Trinidad and Tobago's independence from the United Kingdom, the TTDF is one of the largest military forces in the Anglophone Caribbean.[citation needed]

Its mission statement is to "defend the sovereign good of The Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, contribute to the development of the national community and support the State in the fulfilment of its national and international objectives". The Defence Force has been engaged in domestic incidents, such as the Jamaat al Muslimeen coup attempt, and international missions, such as the United Nations Mission in Haiti between 1993 and 1996.

In 2019, Trinidad and Tobago signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[105]

Foreign relations[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago maintains close relations with its Caribbean neighbours and major North American and European trading partners. As the most industrialised and second-largest country in the Anglophone Caribbean, Trinidad and Tobago has taken a leading role in the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), and strongly supports CARICOM economic integration efforts. It also is active in the Summit of the Americas process and supports the establishment of the Free Trade Area of the Americas, lobbying other nations for seating the Secretariat in Port of Spain.[citation needed]

As a member of CARICOM, Trinidad and Tobago strongly backed efforts by the United States to bring political stability to Haiti, contributing personnel to the Multinational Force in 1994. After its 1962 independence from the United Kingdom, Trinidad and Tobago joined the United Nations and Commonwealth of Nations. In 1967 it became the first Commonwealth country to join the Organization of American States (OAS).[106] In 1995 Trinidad played host to the inaugural meeting of the Association of Caribbean States and has become the seat of this 35-member grouping, which seeks to further economic progress and integration among its states. In international forums, Trinidad and Tobago has defined itself as having an independent voting record, but often supports US and EU positions.[citation needed]

Law enforcement and crime[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago has in recent decades suffered from a relatively high crime rate;[107][108] there are currently roughly 500 murders per year.[109][64] The country is a noted transshipment centre for the trafficking of illegal drugs from South America to the rest of the Caribbean and beyond to North America.[110] Some estimates put the size of the "hidden economy" as high as 20–30% of measured GDP.[111]

Terrorism[edit]

Though there have been no terrorism-related incidents in the country since the Jamaat al Muslimeen coup attempt in 1990, Trinidad and Tobago remains a potential target and it is estimated that roughly 100 citizens of the country have traveled to the Middle East to fight for the Islamic State.[107][108] In 2017, the government adopted a counter-terrorism and extremism strategy.[108] In 2018, a terror threat at the Trinidad and Tobago Carnival was thwarted by law enforcement.[112]

Trinidad and Tobago Prison Service[edit]

The country's prison administration is the Trinidad and Tobago Prison Service (TTPS), it is under the control of the Commissioner of Prisons (Ag.) Dennis Pulchan, located in Port-of-Spain.[113] The prison population rate is 292 people per 100,000. The total prison population, including pre-trial detainees and remand prisoners, is 3,999 prisoners. The population rate of pre-trial detainees and remand prisoners is 174 per 100,000 of the national population (59.7% of the prison population). In 2018, the female prison population rate is 8.5 per 100,000 of the national population (2.9% of the prison population). Prisoners that are minors makes up 1.9% of the prison population and foreigners prisoners make 0.8% of the prison population.

The occupancy level of Trinidad and Tobago's prison system is at 81.8% capacity as of 2019.[113] Trinidad and Tobago has nine prison establishments; Golden Grove Prison, Maximum Security Prison, Port of Spain Prison, Eastern Correctional Rehabilitation Centre, Remand Prison, Tobago Convict Prison, Carrera Convict Island Prison, Women's Prison and Youth Training and Rehabilitation Centre.[114] Trinidad and Tobago also use labour yards as prisons, or means of punishment.[115]

Demographics[edit]

The population of the country currently stands at 1,367,558 (June 2021 est.).[citation needed]

Ethnic groups[edit]

The ethnic composition of Trinidad and Tobago reflects a history of conquest and immigration.[117] While the earliest inhabitants were of Indigenous heritage, the two dominant groups in the country are now those of South Asian and of African heritage. Indo-Trinidadian and Tobagonians make up the country's largest ethnic group (approximately 35.4%);[16] they are primarily the descendants of indentured workers from India,[118] brought to replace freed African slaves who refused to continue working on the sugar plantations. Through cultural preservation many residents of Indian descent continue to maintain traditions from their ancestral homeland. Indo-Trinidadians reside primarily on Trinidad; as of the 2011 census only 2.5% of Tobago's population was of Indian descent.[119]

Afro-Trinidadians and Tobagonians make up the country's second largest ethnic group, with approximately 34.2% of the population identifying as being of African descent.[16] The majority of people of an African background are the descendants of slaves forcibly transported to the islands from as early as the 16th century. This group constitute the majority on Tobago, at 85.2%.[119]

The bulk of the rest of the population are those who identify as being of mixed heritage.[16] There are also small but significant minorities of people of Indigenous, European, Portuguese, Venezuelan, Chinese, and Arab descent.

Arima in Trinidad is a noted centre of First Peoples' culture, including as the headquarters of the Carib Queen and the location of the Santa Rosa First Peoples Community.[11]

There is a Cocoa Panyol community in Trinidad and Tobago whose ancestors were migrant labourers of mixed Spanish, indigenous, and African descent who came from Venezuela between the late 19th and early 20th century to work on the cocoa estates.[120]

Languages[edit]

English and English creoles[edit]

English is the country's official language (the local variety of standard English is Trinidadian and Tobagonian English or more properly, Trinidad and Tobago Standard English, abbreviated as "TTSE"), but the main spoken language is either of two English-based creole languages (Trinidadian Creole or Tobagonian Creole), which reflects the Indigenous, European, African, and Asian heritage of the nation. Both creoles contain elements from a variety of African languages; Trinidadian English Creole, however, is also influenced by French and French Creole (Patois).[121]

Hindustani[edit]

The variant that is spoken in Trinidad and Tobago is known as Trinidadian Hindustani, Trinidadian Bhojpuri, Trinidadian Hindi, Indian, Plantation Hindustani, or Gaon ke Bolee (Village Speech).[51] A majority of the early Indian indentured immigrants spoke the Bhojpuri and Awadhi dialects, which later formed into Trinidadian Hindustani. In 1935, Indian movies began showing to audiences in Trinidad. Most of the Indian movies were in the Standard Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu) dialect and this modified Trinidadian Hindustani slightly by adding Standard Hindi and Urdu phrases and vocabulary to Trinidadian Hindustani. Indian movies also revitalized Hindustani among Indo-Trinidadian and Tobagonians.[122] The British colonial government and estate owners had disdain and contempt for Hindustani and Indian languages in Trinidad. Due to this, many Indians saw it as a broken language keeping them in poverty and bound to the cane fields, and did not pass it on as a first language, but rather as a heritage language, as they favored English as a way out.[123] Around the mid to late 1960s the lingua franca of Indo-Trinidadian and Tobagonians switched from Trinidadian Hindustani to a sort of Hindinized version of English. Today Hindustani survives on through Indo-Trinidadian and Tobagonian musical forms such as, Bhajan, Indian classical music, Indian folk music, Filmi, Pichakaree, Chutney, Chutney soca, and Chutney parang. As of 2003, there are about 15,633 Indo-Trinidadian and Tobagonians who speak Trinidadian Hindustani and as of 2011, there are about 10,000 who speak Standard Hindi. Many Indo-Trinidadians and Tobagonians today speak a type of Hinglish that consists of Trinidadian and Tobagonian English that is heavily laced with Trinidadian Hindustani vocabulary and phrases and many Indo-Trinidadians and Tobagonians can recite phrases or prayers in Hindustani today. There are many places in Trinidad and Tobago that have names of Hindustani origin. Some phrases and vocabulary have even made their way into the mainstream English and English Creole dialect of the country. Still most indo Trinidadian only speak English [124][125][126][127][51][128] World Hindi Day is celebrated each year on 10 January with events organized by the National Council of Indian Culture, Hindi Nidhi Foundation, Indian High Commission, Mahatma Gandhi Institute for Cultural Co-operation, and the Sanatan Dharma Maha Sabha.[129]

Spanish[edit]

Tamil[edit]

The Tamil language is spoken by some of the older Tamil (Madrasi) Indo-Trinidadian and Tobagonian population. It is mostly spoken by the few remaining children of indentured Indian labourers from the present-day state of Tamil Nadu in India. Other speakers of the language are recent immigrants from Tamil Nadu.[131]

Chinese[edit]

A majority of the people who immigrated in the 19th century were from southern China and spoke the Hakka and Yue dialects of Chinese. In the 20th century after the years of indentureship up to the present-day more Chinese people have immigrated to Trinidad and Tobago for business and they speak the dialects of the indenturees along with other Chinese dialects, such as Mandarin and Min.[132][133] J. Dyer Ball, writing in 1906, says: "In Trinidad there were, about twenty years ago, 4,000 or 5,000 Chinese, but they have decreased to probably about 2,000 or 3,000, [2,200 in 1900]. They used to work in sugar plantations, but are now principally shopkeepers, as well as general merchants, miners and railway builders, etc."[134]

Indigenous languages[edit]

The indigenous languages were Yao on Trinidad and Karina on Tobago, both Cariban, and Shebaya on Trinidad, which was Arawakan.[132]

Religion[edit]

According to the 2011 census,[3] Christianity is the largest religion of the country, claimed as the faith of 63.2% of the population. Roman Catholics were the largest single denomination, with 21.60% of the total population. The Pentecostal/Evangelical/Full Gospel denominations were the third largest group with 12.02% of the population. Various other Christian denominations include (Spiritual Baptist (5.67%), Anglicans (5.67%), Seventh-day Adventists (4.09%), Presbyterians or Congregationalists (2.49%), Jehovah's Witnesses (1.47%), Baptists (1.21%), Methodists (0.65%) and the Moravian Church (0.27%)).

Hinduism was the second largest religion in the country, adhered to by 20.4% of the population in 2011.[3] Hinduism is practised throughout the country, Diwali is a public holiday, and other Hindu holidays are also widely celebrated. The largest Hindu organization in Trinidad and Tobago is the Sanatan Dharma Maha Sabha, which was formed in 1952 after the merging of the two main Hindu organizations. Most Hindus in Trinidad and Tobago are Sanātanī (Sanatanist/Orthodox Hindu). Other sects and organizations include the Arya Samaj, Kabir Panth, Seunariani (Sieunarini/Siewnaraini/Shiv Narayani), Ramanandi Sampradaya, Aughar (Aghor), Kali Mai (Madrasi), Sathya Sai Baba movement, Shirdi Sai Baba movement, ISKCON (Hare Krishna), Chinmaya Mission, Bharat Sevashram Sangha, Divine Life Society, Murugan (Kaumaram), Ganapathi Sachchidananda movement, Jagadguru Kripalu Parishat (Radha Madhav) and Brahma Kumaris.[135][136]

Muslims represented 4.97% of the population in 2011.[3] Eid al-Fitr is a public holiday and Eid al-Adha, Mawlid, Hosay, Shab-e-barat, and other Muslim holidays are also celebrated.

African-derived or Afrocentric religions are also practised, notably Trinidad Orisha (Yoruba) believers (0.9%) and Rastafarians (0.27%).[3] Various aspects of traditional obeah beliefs are still commonly practised on the islands.[37]

There has been a Jewish community on the islands for many centuries. However, their numbers have never been large, with a 2007 estimate putting the Jewish population at 55 individuals.[137][138]

Respondents who did not state a religious affiliation represented 11.1% of the population, with 2.18% declaring themselves irreligious.

Two African syncretic faiths, the Shouter or Spiritual Baptists and the Orisha faith (formerly called Shangos, a less than complimentary term)[citation needed] are among the fastest growing religious groups. Similarly, there is a noticeable increase in numbers of Evangelical Protestant and Fundamentalist churches usually lumped as "Pentecostal" by most Trinidadians, although this designation is often inaccurate. Sikhism, Jainism, Baháʼí, Zoroastrianism, and Buddhism are practiced by a minority of Indo-Trinidadian and Tobagonians, mostly by recent immigrants from India. Several eastern religions such as Buddhism, Chinese folk religion, Taoism and Confucianism are followed by a minority of Chinese Trinidadian and Tobagonian, with most being Christians.

Urban centres[edit]

| Rank | Name | Municipality | Pop. | Rank | Name | Municipality | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Chaguanas  San Fernando |

1 | Chaguanas | Borough of Chaguanas | 101,297 | 11 | Sangre Grande | Region of Sangre Grande | 20,630 |  Port of Spain  Arima |

| 2 | San Fernando | City of San Fernando | 82,997 | 12 | Penal | Region of Penal–Debe | 17,952 | ||

| 3 | Port of Spain | City of Port of Spain | 81,142 | 13 | Scarborough | Tobago | 17,537 | ||

| 4 | Arima | The Royal Chartered Borough of Arima | 65,623 | 14 | Gasparillo | Region of Couva–Tabaquite–Talparo | 16,426 | ||

| 5 | San Juan | Region of San Juan–Laventille | 53,588 | 15 | Siparia | Borough of Siparia | 14,535 | ||

| 6 | Diego Martin | Borough of Diego Martin | 49,686 | 16 | Claxton Bay | Region of Couva–Tabaquite–Talparo | 14,436 | ||

| 7 | Couva | Region of Couva–Tabaquite–Talparo | 48,858 | 17 | Fyzabad | Borough of Siparia | 13,099 | ||

| 8 | Point Fortin | Republic Borough of Point Fortin | 29,579 | 18 | Valencia | Region of Sangre Grande | 12,327 | ||

| 9 | Princes Town | Region of Princes Town | 28,335 | 19 | Freeport | Region of Couva–Tabaquite–Talparo | 11,850 | ||

| 10 | Tunapuna | Region of Tunapuna–Piarco | 26,829 | 20 | Debe | Region of Penal–Debe | 11,733 | ||

Education[edit]

Children generally start pre-school at two and a half years but this is not mandatory. They are, however, expected to have basic reading and writing skills when they commence primary school. Students begin primary school at age five and move on to secondary after seven years. The seven classes of primary school consists of First Year and Second Year, followed by Standard One through Standard Five. During the final year of primary school, students prepare for and sit the Secondary Entrance Assessment (SEA) which determines the secondary school the child will attend.[146]

Students attend secondary school for a minimum of five years, leading to the CSEC (Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate) examinations, which is the equivalent of the British GCSE O levels. Children with satisfactory grades may opt to continue high school for a further two-year period, leading to the Caribbean Advanced Proficiency Examinations (CAPE), the equivalent of GCE A levels. Both CSEC and CAPE examinations are held by the Caribbean Examinations Council (CXC). Public Primary and Secondary education is free for all, although private and religious schooling is available for a fee.

Tertiary education for tuition costs are provided for via GATE (The Government Assistance for Tuition Expenses), up to the level of the bachelor's degree, at the University of the West Indies (UWI), the University of Trinidad and Tobago (UTT), the University of the Southern Caribbean (USC), the College of Science, Technology and Applied Arts of Trinidad and Tobago (COSTAATT) and certain other local accredited institutions. Government also currently subsidises some Masters programmes. Both the Government and the private sector also provide financial assistance in the form of academic scholarships to gifted or needy students for study at local, regional or international universities. Trinidad and Tobago was ranked 102nd in the Global Innovation Index in 2023, down from 91st in 2019.[147][148][149]

Women[edit]

While women account for only 49% of the population, they constitute nearly 55% of the workforce in the country.[150]

Economy[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago is the most developed nation and one of the wealthiest in the Caribbean and is listed in the top 40 (2010 information) of the 70 high-income countries in the world.[citation needed] Its gross national income per capita of US$20,070[151] (2014 gross national income at Atlas Method) is one of the highest in the Caribbean.[152] In November 2011, the OECD removed Trinidad and Tobago from its list of developing countries.[153] Trinidad's economy is strongly influenced by the petroleum industry. Tourism and manufacturing are also important to the local economy. Tourism is a growing sector, particularly on Tobago, although proportionately it is much less important than in many other Caribbean islands. Agricultural products include citrus and cocoa. It also supplies manufactured goods, notably food, beverages, and cement, to the Caribbean region.

Oil and gas[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago is the leading Caribbean producer of oil and gas, and its economy is heavily dependent upon these resources.[11] Oil and gas account for about 40% of GDP and 80% of exports, but only 5% of employment.[16] Recent growth has been fuelled by investments in liquefied natural gas (LNG), petrochemicals, and steel. Additional petrochemical, aluminium, and plastics projects are in various stages of planning.

The country is also a regional financial centre, and the economy has a growing trade surplus.[81] The expansion of Atlantic LNG over the past six years created the largest single-sustained phase of economic growth in Trinidad and Tobago. The nation is an exporter of LNG and supplied a total of 13.4 billion m3 in 2017. The largest markets for Trinidad and Tobago's LNG exports are Chile and the United States.[154]

Trinidad and Tobago has transitioned from an oil-based economy to a natural gas based economy. In 2017, natural gas production totalled 18.5 billion m3, a decrease of 0.4% from 2016 with 18.6 billion m3 of production.[154] Oil production has decreased over the past decade from 7.1 million metric tonnes per year in 2007 to 4.4 million metric tonnes per year in 2017.[155] In December 2005, the Atlantic LNG's fourth production module or "train" for liquefied natural gas (LNG) began production. Train four has increased Atlantic LNG's overall output capacity by almost 50% and is the largest LNG train in the world at 5.2 million tons/year of LNG.[citation needed]

Tourism[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago is far less dependent on tourism than many other Caribbean countries and territories, with the bulk of tourist activity occurring on Tobago.[11] The government has made efforts to boost this sector in recent years.[11]

Agriculture[edit]

Historically agricultural production (for example, sugar and coffee) dominated the economy. Sugar cane is the most important crop for Trinidad, earning the most amount of money, and providing work for many people. Some of the sugar produced is eaten in Trinidad but most of it is sold to United Kingdom, Canada, and United States. Cocoa is the second most valuable crop, even covering greater areas than sugar cane. Most farmers grow cocoa to sell to other countries that cannot grow it themselves. Trinidad was once the second biggest producer of cocoa after Ecuador, but this wouldn't last long. As countries in West Africa and South America began growing cocoa at a lower price, Trinidad lost many of its customers.[156] This sector has been in steep decline since the 20th century and now forms just 0.4% of the country's GDP and employing 3.1% of the workforce.[16][11] Various fruits and vegetables are grown, such as cucumbers, eggplant, cassava, pumpkin, dasheen (taro) and coconut, and fishing is still also commonly practised.[16]

Economic diversification[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago, in an effort to undergo economic transformation through diversification,[16] formed InvesTT in 2012 to serve as the country's sole investment promotion agency. This agency is aligned to the Ministry of Trade and Industry and is to be the key agent in growing the country's non-oil and gas sectors significantly and sustainably.[157]

Communications infrastructure[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago has a well developed communications sector. The telecommunications and broadcasting sectors generated an estimated TT$5.63 billion (US$0.88 billion) in 2014, which as a percentage of GDP equates to 3.1 percent. This represented a 1.9 percent increase in total revenues generated by this industry compared to last year. Of total telecommunications and broadcasting revenues, mobile voice services accounted for the majority of revenues with TT$2.20 billion (39.2 percent). This was followed by internet services which contributed TT$1.18 billion or 21.1 percent. The next highest revenue earners for the industry were fixed voice services and paid television services whose contributions totalled TT$0.76 billion and TT$0.70 billion respectively (13.4 percent and 12.4 percent). International voice services was next in line, generating TT$0.27 billion (4.7 percent) in revenues. Free-to Air radio and television services contributed TT$0.18 billion and TT$0.13 billion respectively (3.2 percent and 2.4 percent). Finally, other contributors included "other revenues" and "leased line services" with earnings of TT$0.16 billion and TT$0.05 billion respectively, with 2.8 percent and 0.9 percent.[158]

There are several providers for each segment of the telecommunications market. Fixed Lines Telephone service is provided by Digicel, TSTT (operating as bmobile) and Cable & Wireless Communications operating as FLOW; cellular service is provided by TSTT (operating as bmobile) and Digicel whilst internet service is provided by TSTT, FLOW, Digicel, Green Dot and Lisa Communications.

Creative industries[edit]

The Government of Trinidad and Tobago has recognised the creative industries as a pathway to economic growth and development. It is one of the newest, most dynamic sectors where creativity, knowledge and intangibles serve as the basic productive resource. In 2015, the Trinidad and Tobago Creative Industries Company Limited (CreativeTT) was established as a state agency under the Ministry of Trade and Industry with a mandate to stimulate and facilitate the business development and export activities of the Creative Industries in Trinidad and Tobago to generate national wealth, and, as such, the company is responsible for the strategic and business development of the three niche areas and sub sectors currently under its purview – Music, Film and Fashion. MusicTT, FilmTT and FashionTT are the subsidiaries established to fulfil this mandate.

Transport[edit]

The transport system in Trinidad and Tobago consists of a dense network of highways and roads across both major islands, ferries connecting Port of Spain with Scarborough and San Fernando, and international airports on both islands.[11] The Uriah Butler Highway, Churchill Roosevelt Highway and the Sir Solomon Hochoy Highway links the island of Trinidad together, whereas the Claude Noel Highway is the only major highway in Tobago. Public transportation options on land are public buses, private taxis and minibuses. By sea, the options are inter-island ferries and inter-city water taxis.[159]

The island of Trinidad is served by Piarco International Airport located in Piarco, which opened on 8 January 1931.[citation needed] Elevated at 17.4 metres (57 ft) above sea level it comprises an area of 680 hectares (1,700 acres) and has a runway of 3,200 metres (10,500 ft). The airport consists of two terminals, the North Terminal and the South Terminal. The older South Terminal underwent renovations in 2009 for use as a VIP entrance point during the 5th Summit of the Americas. The North Terminal was completed in 2001, and consists of[160] 14-second-level aircraft gates with jetways for international flights, two ground-level domestic gates and 82 ticket counter positions.

.jpg/220px-Caribbean_Airlines_Boeing_737-800_9Y-TAB_(8504733249).jpg)

In 2008 the passenger throughput at Piarco International Airport was approximately 2.6 million. It is the seventh busiest airport in the Caribbean and the third busiest in the English-speaking Caribbean, after Sangster International Airport and Lynden Pindling International Airport.[citation needed] Caribbean Airlines, the national airline, operates its main hub at the Piarco International Airport and services the Caribbean, the United States, Canada and South America. The airline is wholly owned by the Government of Trinidad and Tobago. After an additional cash injection of US$50 million, the Trinidad and Tobago government acquired the Jamaican airline Air Jamaica on 1 May 2010, with a 6–12-month transition period to follow.[161]

The Island of Tobago is served by the A.N.R. Robinson International Airport in Crown Point.[11] This airport has regular services to North America and Europe. There are regular flights between the two islands, with fares being heavily subsidised by the Government.

Trinidad was formerly home to a railway network, however this was closed down in 1968.[162] There have been talks to build a new railway on the islands, though nothing yet has come of this.[163]

Energy policy and climate change[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago is the region's leading exporter of oil and gas but imports of fossil fuels provided over 90% of the energy consumed by its CARICOM neighbours in 2008. This vulnerability led CARICOM to develop an Energy Policy which was approved in 2013. This policy is accompanied by the CARICOM Sustainable Energy Roadmap and Strategy (C-SERMS). Under the policy, renewable energy sources are to contribute 20% of the total electricity generation mix in member states by 2017, 28% by 2022 and 47% by 2027.[164]

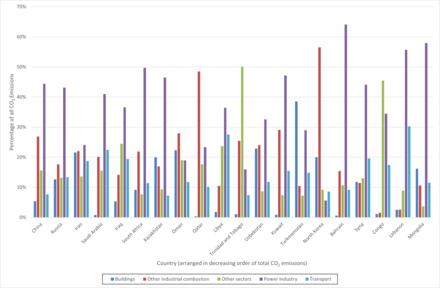

In 2014 Trinidad and Tobago was the third country in the world which emitted the most CO2 per capita after Qatar and Curacao according to the World Bank.[165] On average, each inhabitant produced 34.2 metric tons of CO2 in the atmosphere. In comparison, the world average was 5.0 tons per capita the same year. Over recent years CO2 emissions have declined, so that in 2021 at 21.01 tonnes per capita,[166] Trinidad and Tobago ranked fourth, after the tiny countries smaller than half a million, such as Curacao, are excluded, and is the only non-Middle East country in the remaining worst seven CO2 emitters on a per capita basis.[167]

In terms of emissions intensity of economy (defined as CO2 emissions per unit of GDP), Trinidad and Tobago ranked third globally.[166] Its emissions-source profile is unique amongst the worst CO2 intensity emitters as the so-called "other sectors", which includes: industrial process emissions, agricultural soils and waste, accounts for more than fifty per cent of fossil CO2 emissions, rather than the power industry, other industrial combustion, transport and buildings sectors.[167]

The Caribbean Industrial Research Institute in Trinidad and Tobago facilitates climate change research and provides industrial support for R&D related to food security. It also carries out equipment testing and calibration for major industries.[164]

Culture[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago has a diverse culture with African, Indian, Creole, European, Chinese, Indigenous, Latino-Hispanic, and Arab influences, reflecting the various communities who have migrated to the islands over the centuries.

Festivals and holidays[edit]

The island is particularly renowned for its annual Carnival celebrations.[11] Festivals rooted in various religions and cultures practiced on the islands are also popular. Hindu festivals include Diwali, Phagwah (Holi), Nauratri, Vijayadashami, Maha Shivratri, Krishna Janmashtami, Ram Naumi, Hanuman Jayanti, Ganesh Utsav, Saraswati Jayanti, Kartik Nahan, Makar Sankranti, Pitru Paksha, Raksha Bandhan, Mesha Sankranti, Guru Purnima, Tulasi Vivaha, Vivaha Panchami, Kalbhairo Jayanti, Datta Jayanti, and Gita Jayanti.[170] Christian holidays and observances include Spiritual Baptist/Shouter Liberation Day, Lent, Palm Sunday, Easter, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, Ash Wednesday, Holy Week, Easter Monday, Octave of Easter, Pentecost, Whit Monday, Old Year's Day, New Year's Day, Christmas, Boxing Day, Epiphany, Assumption of Mary, Feast of Corpus Christi, All Souls' Day, All Saints' Day.[171] Muslim holidays include Hosay (Ashura), Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha, Day of Arafah, Mawlid, Ramadan, Chaand Raat, and Shab-e-barat. People of Indian descent celebrate Indian Arrival Day to commemorate the arrival of their indentured Indian ancestors beginning in 1845 and people of African descent celebrate Emancipation Day to commemorate the day their African ancestors were emancipated from slavery. Trinidad and Tobago was the first country in the world to recognize both of these holiday and make them public holidays. The Indigenous Amerindians have their Santa Rosa Indigenous Festival and the Chinese Trinidadians and Tobagonians have the Chinese New Year, although they are not public national holidays.[172] National holidays such as Independence Day, Republic Day and Labour Day are celebrated as well.

Cuisine[edit]

Diversity is also reflected the culinary culture, which bears witness to a variety of influences, including African, Indian, and colonial traditions.[173]

Literature[edit]

Trinidad and Tobago claims two Nobel Prize-winning authors, Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul and St Lucian-born Derek Walcott (who also founded the Trinidad Theatre Workshop). Other notable writers include Neil Bissoondath, Vahni Capildeo, C. L. R. James, Earl Lovelace, Rabindranath Maharaj, Lakshmi Persaud, Kenneth Ramchand, Arnold Rampersad, Kris Rampersad and Samuel Selvon.

Art and design[edit]

Trinidadian designer Peter Minshall is renowned not only for his Carnival costumes but also for his role in opening ceremonies of the Barcelona Olympics, the 1994 FIFA World Cup, the 1996 Summer Olympics, and the 2002 Winter Olympics, for which he won an Emmy Award.[174]

Music[edit]

_2010-09-04_19-02-50.JPG/220px-Theaterspektakel_(2010)_2010-09-04_19-02-50.JPG)

Trinidad and Tobago is the birthplace of calypso music and the steelpan.[176][177][178] Trinidad is also the birthplace of soca music, chutney music, chutney-soca, parang, rapso, pichakaree and chutney parang.[179][180][181]

Dance[edit]

The limbo dance originated in Trinidad as an event that took place at wakes in Trinidad. The limbo has African roots. It was popularized in the 1950s by dance pioneer Julia Edwards[182] (known as the "First Lady of Limbo") and her company which appeared in several films.[183] Bélé, Bongo, and whining are also dance forms with African roots.[184]

Jazz, ballroom, ballet, modern, and salsa dancing are also popular.[184]

Indian dance forms are also prevalent in Trinidad and Tobago.[185] Kathak, Odissi, and Bharatanatyam are the most popular Indian classical dance forms in Trinidad and Tobago.[186] Indian folk dances and Bollywood dances are also popular.[186]

Media[edit]

Other[edit]

Geoffrey Holder (brother of Boscoe Holder) and Heather Headley are two Trinidad-born artists who have won Tony Awards for theatre. Holder also has a distinguished film career, and Headley has won a Grammy Award as well.

Indian theatre is also popular throughout Trinidad and Tobago. Nautankis and dramas such as Raja Harishchandra, Raja Nal, Raja Rasalu, Sarwaneer (Sharwan Kumar), Indra Sabha, Bhakt Prahalad, Lorikayan, Gopichand, and Alha-Khand were brought by Indians to Trinidad and Tobago, however they had largely began to die out, till preservation began by Indian cultural groups.[187] Ramleela, the drama about the life of the Hindu deity Rama, is popular during the time between Sharad Navaratri and Vijaydashmi, and Ras leela (Krishna leela), the drama about the life of the Hindu deity Krishna, is popular around the time of Krishna Janmashtami.[188][189][190]

Trinidad and Tobago is also smallest country to have two Miss Universe titleholders and the first black woman ever to win: Janelle Commissiong in 1977, followed by Wendy Fitzwilliam in 1998; the country has also had one Miss World titleholder, Giselle LaRonde who won in 1986.

Sports[edit]

Olympic sports[edit]

Hasely Crawford won the first Olympic gold medal for Trinidad and Tobago in the men's 100-metre dash in the 1976 Summer Olympics. Nine different athletes from Trinidad and Tobago have won twelve medals at the Olympics, beginning with a silver medal in weightlifting, won by Rodney Wilkes in 1948.[191] Most recently, a gold medal was won by Keshorn Walcott in the men's javelin throw in 2012. Ato Boldon has won the most Olympic and World Championship medals for Trinidad and Tobago in athletics, with eight in total – four from the Olympics and four from the World Championships. Boldon won the 1997 200-metre dash World Championship in Athens, and was the sole world champion Trinidad and Tobago had produced until Jehue Gordon in Moscow 2013. Swimmer George Bovell III won a bronze medal in the men's 200 metres Individual Medley in 2004. At the 2017 World Championship in London, the Men's 4x400 relay team captured the title, thus the country now celebrates three world championships titles. The team consisted of Jarrin Solomon, Jareem Richards, Machel Cedenio and Lalonde Gordon with Renny Quow who ran in the heats.

Also in 2012, Lalonde Gordon competed in the London Summer Olympics where he won a bronze medal in the 400-metre dash, being surpassed by Luguelin Santos of the Dominican Republic and Kirani James of Grenada. Keshorn Walcott (as stated above) came first in javelin and earned a gold medal, making him the second Trinidadian in the country's history to receive one. This also makes him the first Western athlete in 40 years to receive a gold medal in the javelin sport, and the first athlete from Trinidad and Tobago to win a gold medal in a field event in the Olympics.[192] Sprinter Richard Thompson is also from Trinidad and Tobago. He came second place to Usain Bolt in the Beijing Olympics in the 100-metre dash with a time of 9.89s.

In 2018, The Court of Arbitration for Sport made its final decision on the failed doping sample from the Jamaican team in the 4 x 100 relay in the 2008 Olympic Games. The team from Trinidad and Tobago will be awarded the gold medal, because of the second rank during the relay run.[193]

In 2023, Trinidad and Tobago hosted the 2023 Commonwealth Youth Games.

Cricket[edit]

Cricket is a popular sport of Trinidad and Tobago, often deemed the national sport, and there is intense inter-island rivalry with its Caribbean neighbours. Trinidad and Tobago is represented at Test cricket, One Day International as well as Twenty20 cricket level as a member of the West Indies team. The national team plays at the first-class level in regional competitions such as the Regional Four Day Competition and Regional Super50. Meanwhile, the Trinbago Knight Riders play in the Caribbean Premier League.[194]

The Queen's Park Oval located in Port of Spain is the largest cricket ground in the West Indies, having hosted 60 Test matches as of January 2018. Trinidad and Tobago along with other islands from the Caribbean co-hosted the 2007 Cricket World Cup.

Brian Lara, world record holder for the most runs scored both in a Test and in a First Class innings amongst other records, was born in the small town of Santa Cruz and is often referred to as the Prince of Port of Spain or simply the Prince. This legendary West Indian batsman is widely regarded.[195]

Football[edit]

Association football is also a popular sport in Trinidad and Tobago. The men's national football team qualified for the 2006 FIFA World Cup for the first time by beating Bahrain in Manama on 16 November 2005, making them the second smallest country ever (in terms of population) to qualify, after Iceland. The team, coached by Dutchman Leo Beenhakker, and led by Tobagonian-born captain Dwight Yorke, drew their first group game – against Sweden in Dortmund, 0–0, but lost the second game to England on late goals, 0–2. They were eliminated after losing 2–0 to Paraguay in the last game of the Group stage. Prior to the 2006 World Cup qualification, Trinidad and Tobago came close in a controversial qualification campaign for the 1974 FIFA World Cup. Following the match, the referee of their critical game against Haiti was awarded a lifetime ban for his actions.[196] Trinidad and Tobago again fell just short of qualifying for the World Cup in 1990, needing only a draw at home against the United States but losing 1–0.[197] They play their home matches at the Hasely Crawford Stadium. Trinidad and Tobago hosted the 2001 FIFA U-17 World Championship, and hosted the 2010 FIFA U-17 Women's World Cup.

The TT Pro League is the country's primary football competition and is the top level of the Trinidad and Tobago football league system. The Pro League serves as a league for professional football clubs in Trinidad and Tobago. The league began in 1999 as part of a need for a professional league to strengthen the country's national team and improve the development of domestic players. The first season took place in the same year beginning with eight teams.

Basketball[edit]

Basketball is commonly played in Trinidad and Tobago in colleges, universities and throughout various urban basketball courts. Its national team is one of the most successful teams in the Caribbean. At the Caribbean Basketball Championship it won four straight gold medals from 1986 to 1990.[198]

Other sports[edit]

Netball has long been a popular sport in Trinidad and Tobago, although it has declined in popularity in recent years. At the Netball World Championships they co-won the event in 1979, were runners up in 1987, and second runners up in 1983.